- Home

- Sue Ingalls Finan

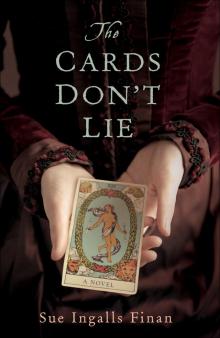

The Cards Don't Lie Page 2

The Cards Don't Lie Read online

Page 2

Tarot: THE HIGH PRIESTESS

Revelation: Entry into a different world of confusion

and bewilderment will lead to a different destiny.

Young Peter Sidney slowly regained painful consciousness. He stifled a moan and tried to hoist his six-foot frame from the floor into a cross-legged, seated position. Once he had achieved that goal, he noticed a puddle of smeared, viscous fluid directly under his right knee. However, the throbbing in his head took precedence. Peter felt the back of his cranium. He kneaded a massive, aching knob, its swelling bulge tender to his touch. Nausea, then, and he vomited. More sticky fluid. Some of it in his lap.

He felt an odd rocking motion but was not sure if it was he or his surroundings that were moving.

“Well, blow me down; you’re finally awake, then, Landsman!” The hearty voice came from about three feet away, and it sounded vaguely familiar.

“Come on, now—up you go. We have to get you presentable. Follow me.”

Peter tried to stand up and get his balance in order to walk behind the voice’s shadowy shape. The man leading him had a sturdy lantern, but it did not shed much light. Peter’s head was dizzy, and his legs were wobbly. He had to plod in a stooped position to avoid hitting the ceiling.

After his eyes adjusted to the darkness, he glanced to his left and right and realized that he was in the hold of a ship. Sea chests, sails, and supplies were packed into the hull’s overcrowded storage space. Continuing to keep his head low, he inadvertently kicked over some kind of container that sloshed water on him.

“Careful of the buckets, Landsman. They’re mighty handy when they’re full and we’re fighting a fire. Of course, we need them when we’re taking on water, too.”

They stopped by a trunk, and Peter noticed that the man had some sort of uniform on.

“This is the slops chest,” the older man announced.

Taking out a key, he opened the chest and selected some of its contents. Handing them to Peter, he said, “Put these on. You’ll find our clothes more suitable than the civilian garb you’re wearing. You’ll be paying me for these garments from your future wages. I am Nathan Scott, the purser.”

Still groggy, Peter sluggishly stripped off his soiled clothing and donned the leggings, shirt, coat, and trousers.

“I heard one of your friends at the pub say that you were the best carpenter in town. For your sake, I hope that’s true. We need a few more buckets with covers made for the men who become ill.”

His eyebrows raised, Peter looked at the smaller man. The purser realized Peter did not comprehend.

“You know, because the sick can’t make it to the head. Here’s your first rule to remember: always use the head. It’s a seat with an opening at the bow. Any unclean behavior on your part will get you severe punishment. Do you understand?”

The purser did not wait for an answer. “You are now in His Majesty’s Navy, and you will, of course, serve the king or be flogged.”

Nathan Scott smiled somewhat at his last announcement, his gums displaying several brown teeth remaining in his mouth. Reaching into his pocket, he pulled out a little pouch. He took out a small sheet of tobacco and bit off a chunk. He chewed on it a bit. Then, with his tongue, he adroitly moved the wad over to rest between his left cheek and gum. Looking back at Peter, he held out the block and said, “Care for a plug of tobacco, Landsman?”

Peter didn’t answer.

“No?” The purser chewed some more, then spat on the floor. “You’ll be getting a tobacco ration yourself soon; just remember that no open flames are allowed onboard. Obvious reasoning, you know. So you’re best off if you chew the stuff.”

Apparently, more of the tobacco plug had dissolved in his mouth, and the purser spat again. “Mmm. And did I mention that you also get a portion of rum every day? Now, I know you like your ale, but I suspect you’ll enjoy the rum, too. Just make sure to add some lime juice to it. Some of our new ‘recruits’ didn’t pay attention to my advice. First they lost their teeth; then their bones and brains deteriorated. Scurvy, you know. Nasty disease.” And, again, Nathan Scott expectorated.

How does the purser know that I like my ale? Peter abruptly recalled where and when he had first heard this man’s voice.

The night before, to mark his sixteenth birthday, he had been having a few ales with friends at the Spotted Dog Pub in Penshurst Village. A group of men entered the tavern and insisted upon “helping” him celebrate by plying him with more alcohol. The Good Fellow of the Hour, they called him, engaging him in conversation and lavishing attention upon him. He’d gone outside to relieve himself, and that was the last he could recollect.

The “generous” men, including Nathan Scott, Peter now realized, were a press gang, looking for able-bodied crew for their warship—the so-called recruits.

He gingerly felt the lump on his head again. They must have smacked him with something solid and dragged him off to the ship.

Still feeling stupefied and now somewhat in shock, Peter followed the purser to the upper deck. While gratefully gulping great lungsful of fresh air, he observed the seamen, intent upon their work, adjusting ropes, inspecting sails, and scouring the deck.

Then he heard spine-chilling howls of pain. They were coming from a man laid out on a mess table and held down by three other sailors. A tub was located nearby.

“Bite down on the musket ball, Charlie!” yelled one of the husky mates holding him down. “It will keep you from biting through your tongue!”

The screaming man was having his left leg amputated.

“Ah, a shame, you know. Charlie had a bad fall from the crow’s nest.”

Peter gave Nathan Scott a blank look.

“Up there!” The purser pointed to a basket lashed to the tallest mast. “Compound fracture. Everyone hoped for the best, and the doc tried to remove the loose bone splinters, but the leg just wouldn’t heal. Putrefied.”

A screw tourniquet had been applied a few inches above Charlie’s knee. While assistants held the outside of the leg in a steady, straight line, the surgeon, looking like a butcher in his long white apron, stood on the inside of the limb, sawing about four inches below the kneecap. The surgeon worked decisively and quickly, slashing through skin, fat, and tendons. Charlie’s agonizing wails continued.

Peter watched, horrified, as the surgeon cut the inside half, making sure to remove all the muscles to the bone. He applied a strip of leather to keep the area clear, before slicing and severing the lower limb. The assistant who had been holding the lower leg turned and tossed the detachment into the tub.

Charlie was now barely whimpering. With a crooked needle, the surgeon tied up the arteries and then removed the tourniquet.

Charlie had lost consciousness.

Peter smelled steaming tar and continued to watch in dismay as the surgeon used boiling pitch to stop the bleeding and seal off the wound.

“Poor Charlie,” said Nathan Scott, shaking his head. “I hope he makes it. He’s a good sailor.”

Tarot: THE FOUR OF SWORDS

Revelation: Stillness needed to assemble one’s

thoughts and organize one’s life.

Marguerite’s baby was about to be added to Jacques’s family vault in St. Louis Cemetery. His tiny cypress casket was positioned next to the whitewashed-brick crypt.

Marguerite was sitting on top of one of the taller tombs nearby and looking down. A small number of friends had come to lend support to the family. She saw them all below, including her self. A servant held a parasol over her head, shielding her from the sun.

Bizarre, she thought. Why, there’s Mother down there, and Père Antoine, too. And there’s me! Yet here I am, up here. But there’s that person—she looks like me and acts like me—down there, with them.

She waved to the people; called to them, Yoo-hoo; look up here! I’m up here!

No response.

They don’t seem to see me up here. How odd. But I’m sure they would like to be up here with me, to see wh

at it’s like!

Marguerite looked around with awe at her surroundings.

What a fantastic view! I can see the river from here, even though it’s eight blocks away! And I can see the carriages parked behind that wall on Basin Street!

She looked downward again. And all these vaults—so many tombs are shaped like small houses. Yes, yes, she chided herself. If the caskets were buried below the ground, the water, when it rises, would make them float to the surface.

She gave a little shrug. Not nice to see Aunt Jacqueline floating off! Plus, this way, with the little houses, we can have multiple burials in one home! Very clever; like a little city, really, with flowers and pretty iron fences and people coming to visit—like those down there!

Marguerite watched as the small group gathered around the de Trahans’ fashionable monument, one of the tallest aboveground tombs.

It’s lovely—for a sepulcher, she thought. Elegantly sculpted images of the poppies of sleep bordering the door. Our de Trahan name carved into stone. A graceful serpent underneath swallowing its tail, the symbol for eternity. Actually, that’s awfully gruesome. But that’s what it’s all about, isn’t it?

And there’s my baby down there, in that casket. So small. So cold. So dead.

She stared at the tomb’s hollow opening. They’re going to bury him—insert him through that opening, into that cavity. His grandparents are already in there. And he’ll be swallowed up. Just like them. Forever.

My beautiful baby boy. And I can’t stop them. If I could, I would make them stop.

So, is this what grief is? Being helpless?

She began to analyze the proceedings. Look at me. I look so very sad, she observed. Everyone does. All that black, she thought. Black shapes embracing one another, exchanging a few words, nodding. Everyone behaving just so in Death’s company.

She felt a chilling presence touch her neck and then crawl down her flesh.

Ahhhhh, Death, and here you are. I know it’s you. Are you watching them, too? There’s the doctor, and three couples from our neighboring plantations. Those two older women? They’re my mother’s friends from church. You already know who their husbands are . . . were—you snatched them several years ago.

Hmm. Père Antoine is starting to pray. But you and I both know that prayers don’t do any good. Silly Père Antoine.

She continued addressing her cold, clammy, clinging specter. Deciding who will be next to capture their last breath?

You can take me. Doesn’t matter. I don’t care. You’ll get no struggle. I’m already released. You can’t do any worse. I surrender. Go ahead!

She looked again at the group below. My self: I wonder, do you see me here? The others can’t—or won’t. I’m obviously already departed, perished, finished. Ha! I’m just not dead yet.

She gazed down at the little assembly again. Death, stare at them with me. Who is next to be cast into a chamber in your little community?

She saw her self step next to her mother, who was fingering a rosary. She saw Sheila reach for her hand and squeeze it. She noticed her self brush a fly away.

Ugh. Flies. I’ll bet they’re your pets, Death. They’re despicable. Their dull buzz. That tedious, irksome drone.

Which is getting louder . . .

Owwww! What’s happening? The buzzing noise—it’s getting worse, pushing down on my brain. Pounding. Stop it!

She saw her self below clenching the crown of her head with both hands. She was pressing her fingers through her black lace veil into her scalp, her palms compressing her temple, squishing her forehead.

This clamor—it’s getting heavier, the pressure. And it’s building, swelling out, bulging in my skull.

“I’m not going away, Marguerite.”

The voice was coarsely unpleasant; sounding mocking, snide.

Who are you? What do you want?

“I am your friend, Marguerite,” the repugnant voice assured her. “I want you to know the truth.”

The truth? The truth about what?

“Your life is useless, Marguerite. What kind of a woman are you? Not much of a wife, that’s for sure. No heir for Jacques. He’s depending on you. But you’ve let him down.”

But I’ve tried! I’ve tried so hard!

“You’ve tried; you’ve tried so hard,” he simpered, mocking her tone.

And then he roared, “You are a failure! Your husband deserves a wife who will give him children.”

Now cajoling, wheedling: “But since I’m your friend, I have a plan for you.”

What are you talking about?

“Why don’t you think about ending your life now? Then you can be with your baby. Down there. I can show you.”

No! Get out of here, you nasty ogre!

A different voice, lighter, even lyrical: “Marguerite, don’t listen to him! You’re grieving; you’re in a dark place. But you must be strong; you must pull through!”

“Huh!” The harsh voice again. “You are weak! Look at those women down there. Three of them are your age. They have children who survived infancy. They’re here to gloat. They’re not your friends. Ask yourself: Why them and not you? You should be envious.”

Marguerite could see her self below, shaking her head. Yes! I’m bitter! And angry, too. Why didn’t my baby live?

She squeezed her eyes shut.

“Because you are useless, Marguerite. And did that silly saint of fertility you prayed to help at all? Did he intervene on your baby’s behalf? He played a cruel joke on you, Marguerite. You should punish him!”

Opening her eyes again, she pursed her lips and clenched her fists. You’re right! How dare he! I will demand that Père Antoine put St. Anthony’s statue upside down in a corner of the church!

“That’s the spirit! Now you’re on the right track!”

And I said the rosary every day and made generous donations to the church’s poor box. What good did it do me? So unfair!

“Now, slow down here, Marguerite!” It was that second voice again. Gentle. Tender.

But Marguerite was livid.

What! Marguerite demanded. That first voice was right. She wanted to rage, destroy.

And the throbbing pressure in her head was becoming more severe.

“You know many women lose their babies—some in childbirth—and how many others die before their fifth birthday?” the second voice said soothingly. “Those women down there are your friends. They were your classmates at the Ursuline Convent School. You have known them for a long time. And they have lost children, too. They know your sorrow. They are here to comfort you, just as you were there for them. Remember!”

Yes, but . . .

“This sadness will never go away, but it will become less painful. And eventually you will want to ask for St. Anthony of Padua’s help again. You must have faith! You must think about the future! St. Anthony will help you conceive once more and ensure safe childbirth. Don’t listen to the evil one.”

“Nonsense! There is no future. Silly St. Anthony is never going to listen to you. You will never have another child. Because you are worthless, Marguerite.”

“Don’t listen to the Devil, Marguerite! Trust me!”

“Bah! You know I’m right! None of those people down there cares about you. And look at all that praying you did. God doesn’t even care about you! Forget about that silly saint; forget about those people down there. Just end it now!”

Marguerite took a deep breath.

“Destruction. Easy to do.”

“No, Marguerite, no!”

From her high perch, Marguerite looked down again upon the assembly. She saw her self grip the tip of an iron railing tightly. A jagged thorn from a climbing rosebush pierced her glove. She watched as a small red drop appeared.

Blood.

The voices were still. The heavy pounding throughout her head was subsiding. Also, she was becoming fully aware of her body’s senses down below, especially the stabbing pain in her finger. Yet here she was, still above the crowd. Fe

eling quite unsteady. In both places. Panic.

I’m frightened. What’s happening to me?

She saw her self inspect the blood from her finger and then turn to grip the iron fence again with both hands. Her awareness of her body below was growing more tangible.

More blood. And not from her finger. She knew she was still weak from childbirth, and now she perceived heavy bloody discharges accompanying her every move.

The fear became dismay. Damn! What if my rags are saturated? What if there’s blood on the ground below my skirt? Good thing I’m wearing black. But what if it shows? How appalling!

Although she knew that Père Antoine was conducting a very short ceremony, she was suddenly aware that her body couldn’t remain standing there. She saw her legs wobble. How humiliating if she were to faint. And with blood running down her legs. She tried to hold on to the railings to balance. I must brace myself; I can’t let myself go.

Death’s voice came back and laughed. “Of course you can, Marguerite! Do it! Hit the ground. Serves you right! Do it, Marguerite!”

“No! Stop it!” she yelled back at him. “I’m in control! Now leave me!”

Sheila looked at her daughter in surprise. “Are you all right, dear?” she whispered.

Marguerite’s eyes opened wide as she realized that she was grounded. And there seemed to be only one of her. Just to be sure, though, she raised her head and looked up at the taller tomb nearby. No one was sitting there, looking back at her.

Still weak, she tried to take a deep breath.

And gagged.

Despite the fragrance of the roses and flowers planted by the families who owned each tomb, she was becoming nauseated. The smell of the decomposing corpses in the burial chambers was overwhelming. She choked down the bile.

I must remain strong.

Sheila grabbed Marguerite’s arm and helped her stagger to the cemetery wall. She leaned upon it, still unsteady.

“You will survive, Marguerite; you will survive.” The message was softly reassuring.

And then absent. The voices, the pounding, and the aching in her head ceased. Marguerite looked up again at the top of the pediment tomb. Empty.

The Cards Don't Lie

The Cards Don't Lie